A Case of Trust: What South Korea’s Response to COVID-19 Teaches Other Countries

The COVID-19 pandemic is possibly the biggest public administration challenge in modern history. Despite the global nature of the disease, the public management of the disease varies among countries. Largely, Western countries initially adopted a softer approach relying on herd immunity, compared to the more dynamic approaches of countries like China. However, both approaches had their own drawbacks.

South Korea in particular has been applauded for its successful control of the pandemic. Till date, the country has reported just over 300 deaths, and there are relatively few overall infected patients. We spoke to Professor M. Jae Moon of Yonsei University, who is a member of the COVID-19 Response Research Team of the National Research Council, South Korea, about the South Korean efforts in tackling the pandemic, and about his recent article on policy problems and governance challenges, published in Public Administration Review.

M. Jae Moon is professor of public administration and dean of social sciences at Yonsei University, South Korea. He is the director of the Institute for Future Government and has been a member of the COVID-19 Response Research Team of the National Research Council of South Korea.

Q: What were the first few days of the outbreak like in South Korea?

Prof Moon: South Korea reported its first case on January 20, and, like other countries, saw a surge in cases soon after. February 19 was when the cases reached a worrisome peak with 909 new cases, mostly in Daegu and Kyungbook. The Korean government announced its lowest crisis alert level (Level 1) when the first confirmed case was found in Wuhan, China, and later continued to adjust its levels till the highest level (Level 4) was reached on February 23.

Q: How did the government respond? Did they follow a hard approach, or a milder one like those adopted by European countries?

Prof Moon: Neither, actually. The South Korean government decided to go with a unique, agile-adaptive approach. They proactively identified each infected case and quickly worked on exposing associated potential cases. The government tested more than 4,099 people per million from the beginning of the outbreak, a number much higher than that of the United Kingdom, Japan, and the United States. This approach let the government flatten the coronavirus curve by slowing down and controlling the contagion speed.

Q: Why do you call this the agile-adaptive approach?

Prof Moon: Well, the South Korean government was adaptive while handling new situations and quickly formed alternative solutions in uncertain circumstances. For example, when the number of infected but “mild-symptom” patients increased, the government improvised by using training centers and public facilities to accommodate them. This adaptative approach was largely possible because the South Korean government gave more value to “science” over “policy,” by making key decisions based on scientific evidence rather than political calculations.

Q: But this is not the first outbreak that South Korea has dealt with in the recent past. There was an outbreak of MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome) in 2015 that was not managed very well. Did that experience help the South Korean government today?

Prof Moon: Yes, very much, I would say. Over the course of the 2015 MERS outbreak, South Korea reported the second highest number of infected patients globally. However, to avoid any widespread panic, the government initially did not disclose all necessary information. This had a negative effect, leading to public dissatisfaction. After the MERS outbreak, the government evaluated the learnings from the experience; it upgraded the powers and duties of the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) and increased the number of experts affiliated to KCDC.

Q: How did this help?

Prof Moon: For one, the massive scale of testing during the COVID-19 pandemic was possible because the government was already well-prepared due to its experiences with MERS. On another front, the government employed a full transparency policy this time, and citizens were regularly notified about everything, right from the number of cases in their area to the availability of masks at the nearest drugstore.

Q: Speaking from a policy standpoint, wouldn’t such a transparent approach be detrimental if the government fails to succeed in management? Wouldn’t the rising number of cases cause concern?

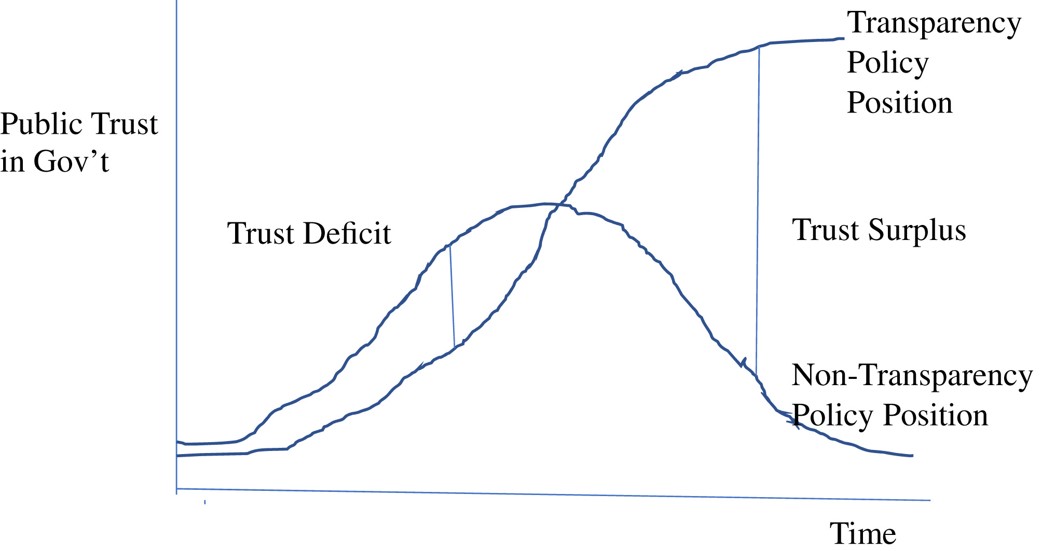

Prof Moon: Initially, yes, the information can cause a “trust deficit.” But in the long run, the public accepts the government as a reliable source of information, resulting in a “trust surplus” (Figure 3 from my paper). This is exactly what happened in South Korea as well; the South Korean government’s policies helped the citizens trust the government to filter out fake news and rumors around COVID-19 and increased the credibility of the KCDC in the long run. This also helped increase cooperative participation in protocols like social distancing. In contrast, such countries as Japan and U.S. have recently begun to experience trust deficit due to the politicking of COVID-19 issues.

The hypothetical curve of public trust when comparing transparent and non-transparent policies

The hypothetical curve of public trust when comparing transparent and non-transparent policies

(Source: Moon. Fighting COVID-19 with agility, transparency, and participation: wicked policy problems and new governance challenges. Public Administration Review. 2020.)Q: What was the public reaction to the South Korean government’s transparent policies and proactive measures?

Prof Moon: Relatively speaking, the public was extremely cooperative, actively participating in sanitization and social distancing protocols, and this was crucial for the successful control of the pandemic. Of course, like anywhere else, it is not practical to expect one-hundred percent compliance to protocol. For example, initially, there was a shortage of essentials like masks due to illegal stockpiling. Nonetheless, the government did respond by rationing such supplies to citizens, alleviating their worries and gaining their trust even more.

Q: Like the MERS, do you think COVID-19 also has a lesson to teach in policymaking?

Prof Moon: Yes, absolutely. The way South Korea used its learnings from MERS during COVID-19 management, countries worldwide can quickly learn from the initial COVID-19 management failure, focus on administrative and policy capacities to minimize potential damage, and prepare for future challenges with minimal disruption of quality of life in free and open democratic societies. This will require a holistic approach, through the input of not just politicians and policymakers, but scholars and practitioners as well.

Of course, fighting against COVID-19 is still an ongoing task. A ”good” mid-term performance does not necessarily guarantee a great final performance unless the Korean government continues to maintain its effective agile-adaptive approach along with close collaboration with medical communities and citizens. The Korean government also needs to pay increasing policy attention to economic and social recovery of the current crisis.

Updated in August 2020

Recommended Articles

Professor Sangyup Choi and Myungkyu Shim

Researchers Show How Uncertainty in Inflation Expectations Affects Economic Growth

Professor M. Jae Moon

The evolution of E-Governance: Professor M. Jae Moon’s contribution

Professor Jeonghye Choi

Studies Show Social Interaction Is Bigger Motivator than Money for Sustained Purchase Behavior